william david brooks

Private William David Brooks, service number 1063143, was born in the Belmont Township in Ontario on February the 23th, 1983. He was a farmer and was not married; he worked with his father at the family farm. He and his family were Methodists. Brooks enlisted on February 28th, 1917 in Peterborough. Brooks was considered fit by the medical doctor that examined him. He had a dark complexion, with blue eyes and black hair. When Brooks enlisted he was 5-foot 8-and-a-half and weighed in at 145 lbs. In both eyes Brooks had 30 vision. Brooks was 34 years of age when enlisting. His only military experience was one year in the 15th Argyle light infantry. His agreement was to serve one year, or during the war that then existed between Great Britain and Germany should that war last longer than one year, and for six months after the termination of that war provided. His mother and next of kin was Phoebe Jane Brooks, as he had no children nor spouse to pass down his belongings to. Brooks was assigned duties as a private in the Canadian Infantry (Central Ontario Regiment), and traveled with the 54th Battalion. The 54th battalion was an Infantry Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force during WWI. Brooks' death was caused by a piece of shrapnel from an artillery shot over head. The injury occurred on the first of October, but after four days of attempting to heal and recover, the wound got the best of William. Brooks died at the age of 35, in France (presumed) on October 4th 1918.

Etaples Military Cemetery is the largest CWGC (Commomwealth War Graves Commision) cemetery in France. It is located on the former site of a large military hospital complex used by the Allies during the First World War.

Etaples Military Cemetery

This cemetery holds over 11,500 dead from both World War One and World War Two. During the First World War, the area became the largest British military base in the world with a huge complex of reinforcement camps and hospitals for all troops of the British empire.

Brooks is buried in the Etaples military cemetery; pas de Calais, France, grave reference LXVII. H. 8. Etaples is a town about 27km south of Boulogne. The cemetery is to the north of the town, on the west side of the road to Boulogne.

This is the path planed for the battalion to take whilst fighting through France.

Brooks was assigned duties as a private in the Canadian Infantry (Central Ontario Regiment), and traveled with the 54th Battalion. The 54th battalion was an Infantry Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force during WWI. the battalion was authorized on the 7th of November 1914. The men embarked for Britain on the 22nd of November the following year. After coming together and regrouping in Britain the battalion was off to France to being their duties in battle. The battalion fought as a part of the 11th Infantry Brigade, 4th Canadian Division in France and in Flanders until the end of the war.

These pictures are from a news article about the Norwood memorial. Brooks is displayed and commemorated on this memorial. The memorial was first displayed on June 6th 1924. The memorial was brought up and introduced by The Imperial Order of the Daughters of the Empire (I.O.D.E.), who organized the fundraising and the powerful ceremony which included an invitation to all veterans of all wars. In the picture to the right, Brooks' name is listed 7th name down underneath the photo.

This a letter written from brooks, home. He wrote this directly to his mom but he wrote for his mother and father.

This second letter is a letter sent to Brooks from his mother Phoebe Jane Brooks. This letter was a reply to the message that David sent home.

The Great War from a Medical Standpoint

From a medical standpoint, World War I was a miserable and bloody affair. When America first joined the war in 1917 they did not have an established medical system. They copied the system that the French and English did within the past three years. This system arranged medical staff in a practical manner in three to four steps. Stretcher-bearers first came into contact with the wounded and moved them from trenches to waiting ambulances. Though the treatment was nothing like what we have today, this treatment often saved lives. Lieutenant Andrew Green wrote to friends in Raleigh praising the stretcher-bearers who carried him over one mile through enemy shell fire after he was wounded in the leg.

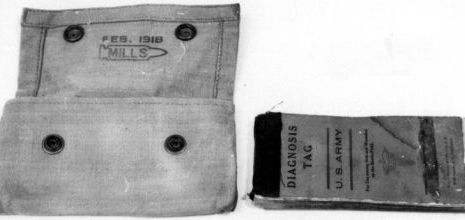

"Diagnosis tag book." 1917-18. Made by William J. Brewer. NC Museum of History.

Motorized transportation proved to be the most efficient way to transport the wounded. The ambulances would rush thm wounded soldiers to the mobile dressing stations or field hospitals that followed the advancing and retreating troops. After that the severely injured were taken to base hospitals far behind the line. World War I was the first conflict to see the use of deadly gases as a weapon. Gas burned skin, irritated noses, throats, and lungs. It could cause death or paralysis within minutes, killing by asphyxiation. As soon as troops learned this they were required to wear masks. Even having the fumes in their clothing could cause blisters, sores, and other health problems.

This is recorded footage of a war patient with war neurosis (shell shock/PTSD) before and after treatment.

Before Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) this same mental illness was called shell shock or War Neurosis. The term shell shock was first coined by a Medical Officer called Charles Myers. Originally shell shock was believed to be caused by the drilling stress on the body of the explosions of artillery shells. Further study after the war has shown that shell shock or PTSD is from a horrific amount of stress or overload of exposure to Traumatic events.